Pakistan's Literacy Landscape: Numbers, Insights, and Solutions

The government's absence from the scene has prompted non-profit entities like TCF to step in progressively. If it can't deliver quality education itself, why not aid these entities

It's a famous saying that data doesn't lie, a statement that holds especially true for Pakistan. When one looks at the abysmal numbers and compares them to dismal on-ground conditions, nothing but one thing becomes apparent: data doesn't lie.

Pakistan's literacy rate currently stands at 62.3%. For someone belonging to a developed country, this statistic would appear to be shocking. Most Pakistanis, however, won't be perturbed at all by this 'revelation' because, in our daily experience, we deal with children who haven't been to school at all.

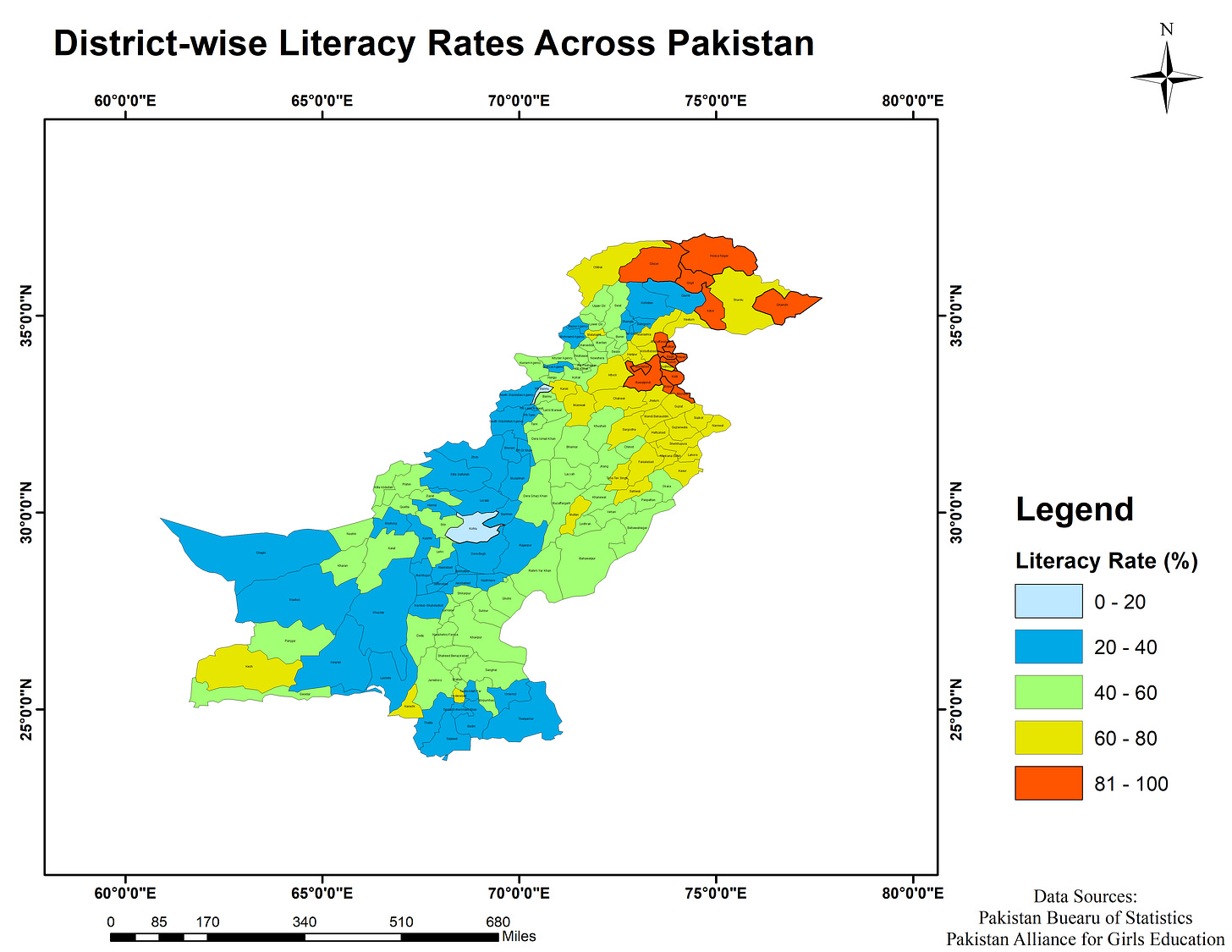

Much like others, I always believed that the lower literacy rates emanate out of peripheral regions and that the urban megapolises stand atop the ladder for literacy numbers. However, a couple of weeks ago, I read somewhere that Azad Kashmir and Gilgit have literacy rates higher than the rest of Pakistan. I found this surprising because the regions mentioned are among the peripheries, and to have literacy numbers higher than Islamabad or Karachi is one pleasant stat on its face.

So, I started digging up the numbers to see the picture more accurately. What I found was pretty interesting, which I thought would be worth sharing on this platform.

The statistics indicate that districts in AJK and GB exhibit literacy rates approximately 20% higher than the rest of Pakistan. This goes against the thinking most of us have; that merely we, from mainstream Pakistan, realize the importance of education, while everyone else from these peripheries lives in dark ages, so we need to bring 'civilization' to them. This argument may perturb most of you, for it goes against your deeply held convictions. However, think a bit about this, and you'll realize the premise of my argument. The most viral news story of the previous year was the Swat Cable Car accident, which saw five students and their teacher rescued from a hung cable car. Why did they board the cable car, knowing its dismal condition? Because they had to go to their school, but no way to cross the river except using the cable car. Day after day, they had to cross the river using that treacherous cable car to reach their school.

This sordid tale depicts two critical aspects; first, infrastructure throughout the country, particularly in the peripheral regions, is as deteriorated as it could get and needs immediate government intervention. Secondly, and more importantly, it depicts the demand for education on the part of the local community. The episode highlights that even the poorest among us want their children to be well educated, suggesting that the blame for low literacy rates in the country solely lies with the state. If the state doesn't offer economic incentives, families from lower-income backgrounds may not send their kids to school, so the literacy rate will likely stay the same.

Another surprising observation in the data was nearly equal literacy rates among men and women, even in places one doesn't expect them to see, like Balochistan. Even though literacy rates stand at the lower end of the spectrum for both genders, an equivalent literacy rate once again goes against our preconceived notion that the literacy rate among women is at much lower levels throughout the country when compared to men. However, a question worth exploring could be how female literacy rates have evolved in Pakistan over decades. Maybe it's a topic worth discussing in some other blog post.

Keeping GB and AJK aside, literacy rates are dismally low across the country, depicting a dysfunctional educational system. The hallmarks of this broken system include ghost schools, inadequate infrastructure, poor teaching standards, and local political intervention. Most of us believe that all the problems chasing the educational sector will evaporate into thin air merely by increasing the budget allocated for education. False. After the 18th amendment, the subject of education lies with the provincial governments, which have budgeted a decent amount for education. For context, during the 2022-23 fiscal year, the government of Punjab earmarked Rs. 493 Billion for education. Despite this, we've seen no reasonable change in literacy rates. Reason? The temptation to handle everything from Lahore, Karachi, Peshawar or Quetta with the aid of administrative apparatus, i.e. provincial bureaucracy. The "Babus" treat the wound with only medication they know, "quick fixes."

Such negligence on the part of the provincial government necessitates the localization of education at the UC level. More proactive participation from the local community, who know the importance of quality education, can lead to improved literacy rates at the local level while also keeping school admin on their toes to avoid any negligence.

I've earlier mentioned Balochistan in an optimistic light. Now let's look at the province through a more pessimistic lens. Statistics from Balochistan place it near ex-FATA regarding literacy rates, depicting alarmingly low numbers. However, the southern districts of the province present a different reality. The literacy rates in those districts are comparable to those in Punjab, depicting the prevalence of educated youth in the region. However, the policy circles also need to view this stat in a different light. As the education levels rise in an underdeveloped area, so does desperation, which can put the educated youth on dangerous avenues. That's why the state should address the demands raised by Baloch protestors sitting in Islamabad. Perhaps this is the sole method to heal the wounds of the disenchanted educated youth from the province.

The small enclaves of success at the local levels don't suggest anything worthwhile at the national scale. It's time for the state to tame the horse of a dysfunctional educational system, curb systematic inefficiencies, and provide means for every child to get a quality education. However, the pessimist in me doesn't foresee the government fulfilling any of these responsibilities. The government's absence from the scene has prompted non-profit entities like TCF to step in progressively. If it can't deliver quality education itself, why not aid these entities in their mission to make quality education accessible for everyone in Pakistan?